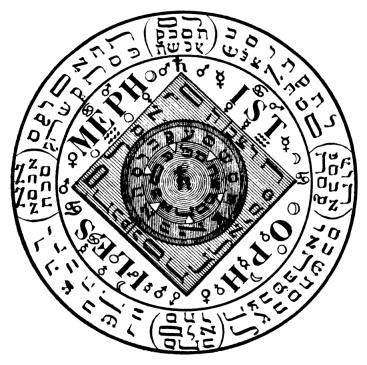

Certainly, the closest literature and even film ever came to presenting an actual Satanic message in the Modern sense involves the history and myth surrounding the personality of Johann Faust. The Faustian Myth in many ways set the stage for the development of the Modern World in which humanity, with the use of “magic,” stepped on the stage of history and cosmology to become an active agent in the creative act. The legends of Faust at first emerged in German folklore as a cautionary tale. The scholar/magician Faust sells his soul to the Devil (i.e., the demon Mephistopheles) to gain knowledge, power and pleasure. In some versions of the tale the contract or pact was to last 24 years, after which time the Devil came to claim his due and the body of Faust is found lying on a dung heap. These legends were prevalent beginning in the 16th century, and along with them there also appeared a plethora of actual grimoires purporting to be those used by this semi-legendary figure to make his pact. The existence of these grimoires demonstrate that the myth was more than mere stories. In 1808, the greatest German man of letters, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe began publishing his magnum opus, Faust, in two parts. This work of literature was an example of a Faustian tale told by a Faustian personality. In the end, Faust is not condemned to Hell, but is saved by the angel who in life had been the girl named Gretchen — the “eternal feminine” — who pulls us ever onward. Goethe gave form to the Myth of the Modern, the Faustian Age.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle established the concept that the Good [Greek Agathon] of anything is determined by the question of whether that thing is doing what it is uniquely or especially suited. The eye is in its good when it sees, the ear is in its good when it hears. What then is that for which the human being is primarily suited? Man is in his good when he thinks. Those things which Faust acquires by means of his pact are all aspects of the good on Humankind— knowledge, power and pleasure. Therefore, in the Faustian Mythology, Faust is not pursuing evil, but rather the good on a philosophical level.

The roots of the Faust legend lie in the actual life of a German scholar and alchemist who was born in the late 1400s and died around 1540. He supposedly met his demise as a result of an explosion linked to an alchemical experiment. He quickly became the focal point of legends and myths regarding sorcery and a pact with the Devil. Actual grimoires appeared in the “Faustian tradition.” These were printed and eventually collected in Johan Scheible’s multi-volume work Das Kloster published between 1804 and 1850).

The Faust-theme has been widely employed in films from F.W. Murnau’s 1926 masterpiece Faust to the classic 1967 comedy Bedazzled. Most, such as the 1967 adaptation of Christopher Marlowe’s 1592 drama The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus simply titled Doctor Faustus by Richard Burton, follow the conventional path of showing the life of Faust as a cautionary (and even horrific) tale of the results of making such pacts with Satan. More fantasy-oriented and even comedic variations also include The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941), a film noirentitled Alias Nick Beal (1949), Damn Yankees (1958). Perhaps the most compelling and intriguing adaptations is found in the 1987 film Angel Heart (adapted from the 1978 novel Falling Angel).

The story of Faust is usually told as a tale of horror and dread in the face of the temptations of gaining the knowledge, power and pleasures offered by means of making a pact with Satan. It is only when we get a version of the story more or less told from the perspective of a Faustian man, Goethe, that we gain more philosophical insight.