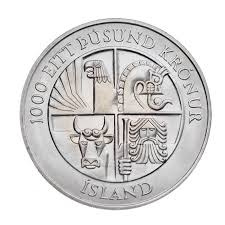

In Iceland one of the most famous complex symbols for the nation, and for the land, is a set of four mythic creatures called the landvættir— the “land-wights.” They are, for example represented on the Alþingishús (Parliament House) and on many Icelandic coins. Their images appear thusly on a thousand kronur coin:

Here we see a dragon or serpent, an eagle, a bull and a humanoid figure.

At first glance the symbols might appear to have been influenced by Astrological symbology— the Lion (Leo), Man (Aquarius), Eagle (Scorpio), and Bull (Taurus) later borrowed in the Middle Ages by the Christians to signify the Four Evangelists: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. This is, however, clearly not the case. The symbols do not fit, and the lore proves otherwise.

The clearest explanation of the lore of the Icelandic landvættir is contained in the Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar (ch. 33) which is found in the Heimskringla corpus. There we read of a sorcerer (kunnigr maðr) is sent by King Harald Gormsson of Denmark to do reconnaissance to see if the island can be invaded. The sorcerer goes out in the shape of a whale and when he comes to the island: “He saw that all the mountains and hills were full of land-wights, some big and some small.” First he swims up the Vápnafjord (in the east): “Then a big dragon (dreki) came down the valley, followed by many serpents, toads and adders that blew poison against him.” The sorcerer then heads to the northern part of the island and enters the Eyjafjord: “And there flew against him a bird (fugl) so large that its wings touched the mountains on either side of the fjord, and a multitude of other birds besides, both large and small.” He continued swimming around the island and in the western part of the land he entered the Breiðafjord: “Then came against him a big bull (griðungr), wading out into the water and bellowing fearfully. A multitude of land-wights followed him.” So the sorcerer continued to the southern part of the island and tried to come ashore at Víkarsskeið: “Then came against him a mountain giant (bergrisi) with an iron bar in his hand, and his head was higher than the mountains and many other giants were with him.” From the sorcerer’s report the king saw that it was not feasible to attack Iceland because it was well-protected by its land-wights. This is certainly the oldest systematic written description of the landvættir of Iceland.

It should be noted that the idea of the landvættir was certainly imported to the previously uninhabited island of Iceland by the Norwegian settlers. It is most probable that such landvættir were at one point commonly believed to have inhabited all Germanic lands. This is further evidenced by the fact that the serpent or dragon heads commonly used on Viking ships were intended to drive off the landvættir of countries being raided by the Vikings. This was why Icelandic law was later to mandate that the dragon heads had to be removed from the ships when they approached Iceland itself.

The possible operative uses of the images of the landvættir have probably already suggested themselves to most Runers. Obviously these images can be used to establish secure spaces either on a permanent or temporary basis. For example, the images can be incorporated in the performance of the Hammer-Rite, or similar ceremony. Each of the images should be studied in its own right for the operative uses.

The way in which the landvættir work in a galdr-sense is not all based on terrorizing an enemy or potential enemy. Clearly each of the landvættir imparts a special aspect which as much gives strength and security to the home-base as it does to terrify any adversary. The dragon (dreki) fulfills a terrifying function, but the “bird” (probably an eagle or earn) provides insight and knowledge, the bull provides well-being and wealth and the bergrisi, with his bar of iron, is a storehouse of memory and forms as well as potential danger to enemies. Note the correspondences between these symbols and the cosmological map of Yggdrasill and the system of elements suggested from Snorri’s account of the birth of the world in the Edda.